I am going to try not to use this blog as a sounding board to expunge my rants about the delays in our house renovations. However it has been the most frustrating summer, with the builders having moved on to another project instead of waiting for the interminable process of hanging around for Lambeth Planning Department to get their act together.

While the house lies empty, and the front garden grows evermore jungle-like with weeds sprouting through the brickwork, I have been busy behind the scenes. I’ve been hidden away in the Archive Library for Lambeth, digging out old plans of the houses on the road in order to put together our argument for our second application.

We want to renovate the house and three of the four phases we are intending to carry out require permission from Lambeth. The decision for two of the three phases are not down to the discretion of the planner and therefore should be straightforward – they merely require a certificate for Lawful Development which is a standard permission given under the remit of Building Control. However the first of our straightforward applications was – to my chagrin – rejected. Lambeth decided this on the basis that the side of the house is the principal elevation, because its front door is on this side and about 50 years ago someone changed the address of the house to the side road instead of the front road.

Unfortunately the decisions for all three phases are going to hinge on this one interpretation of “principal elevation” and unless I can persuade Lambeth that the front is the main elevation, then we are going to have a string of rejected applications from here on in. If, however, Lambeth actually bother to pay attention to the fact that we are a bit of an anomaly and they allow common sense to determine their next move, then we’re onto a winner for all three phases. It really is an exasperating all-or-nothing situation.

So I have been taking copies of every relevant plan from the late 19th century archives when these houses were built. And it has been a fascinating process, not least because one starts to get a sense of the Victorian property speculators building these houses. Census returns between 1801 and 1911 show that the population of Great Britain almost quadrupled, rising from about 10 million people to 36 million. It is no wonder then that property speculation became big business, eventually creating a glut of houses for the more well off. Often living locally, these property developers would put up the funds for three or four adjacent houses. Thus you might get a terrace of nine houses, like ours, but with three different owners and displaying slightly different styles in the window, door and internal detail to show the individuality brought by each architect. The two end houses for the terrace might have the same overall architectural proportions, but will naturally be designed to a different floorplan and roofline because they are the two semi-detached bookends on the run of houses.

Our house is just one of those bookend properties with a matching house at the other end of the run. Both the bookends on this terrace have their front doors on the side but only ours carries a different address than all the others on the terrace. Going back through the census records to see how people have recorded their addresses, I could pinpoint the change of our house from Dodbrooke Road to Thurlestone Road in 1963. But why? Unfortunately the census does not record reasons, simply the results. What might seem strange is that there was a number going spare in the middle of Thurlestone Road, just at the point where our house was. In fact it seems that the owner of our house got their idea for changing the address from the house across the road, which a decade earlier had given up the number we eventually inherited.

As a result the records for our house are a bit of a muddle with the Ordnance Survey maps to this day showing the old number with our current number being shown on the house across the street, which is mightily confusing. And yet, one might have thought that at some point in a period of more than 50 years, Lambeth might eventually twig that the two addresses relate to the same property, but no! When we bought the house, I was the one to bring their attention to this discrepancy in their records. How I wish now I had never been so efficient, as I probably could have got away with having every application rubber stamped under the original address and Lambeth would never have realised that it no longer existed.

Oh well, we live and learn.

In the spirit of learning, I went back to the Archive Library to research any information that might help me argue the case for treating the house as part of the terrace to which it is is so obviously the bookend and hence conceding the bleeding obvious – that the front is the front.

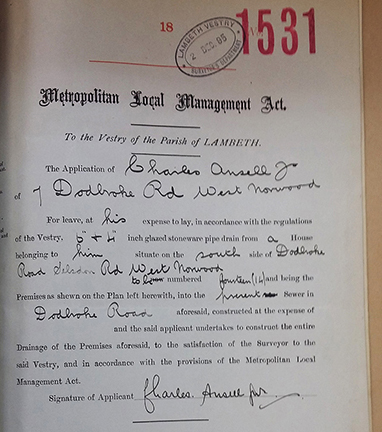

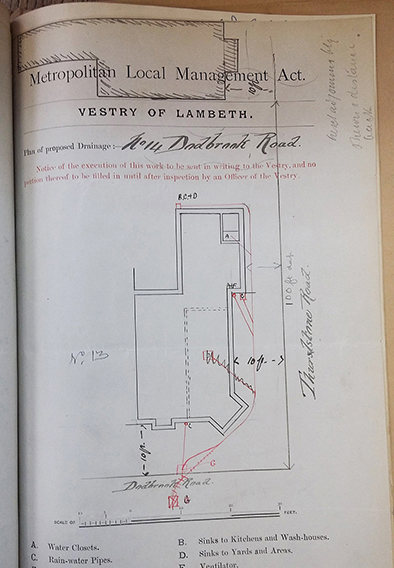

The Victorians were the first to introduce the beginning of what we know now to be Building Regulations. And it turns out that, while they were not interested in the look of the building or the integrity of the architecture, they were obsessed by the drains! From the middle of the 19th century, there was an increased importance placed on sanitation in properties and by the end of the Victorian era, hot and cold running water was available in the majority of homes. Outside toilets were constructed and enclosed sewers were built under the property. And one can see that by 1897 – when our house was built – the most important document for the local authority was a plan of the drains. This quite clearly shows the drains in line with all its the other drains on that terrace and joining to the main sewer on the front road not the side.

Well, this all adds up to what I think is a convincing argument that, despite having its door and address on Thurlestone Road, the historical documents (as well as common sense) tell us that the house is clearly part of Dodbrooke Road. Having done all this work myself, I then employed a Planning Consultant to make the application for me, assuming that an expert would know all the procedural requirements and how to state the case in a presentable form.

I was rather discombobulated to be charged a hefty £2000 for the Planning Consultant to copy and paste my argument (almost verbatim) onto her letterheaded paper for the application. It was rather mortifying to be charged for every six minutes of her time when I had to write three emails back to her listing all her spelling mistakes and grammatical errors; more horrifying still that on the third draft she was still spelling “principal” (as in the “principal elevation” at the core of our argument!!!) erroneously as “principle”…

Still, if her logo and letterhead lend the necessary weight to my argument to convince Lambeth, then it will be money well spent. We find out their judgement on the 18th of October.