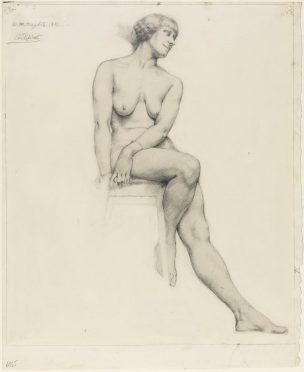

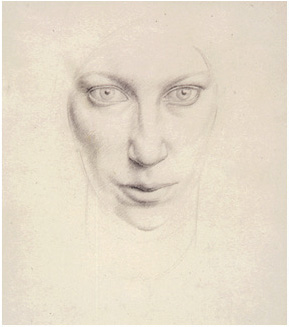

A recent visit to the Dulwich Picture Gallery opened my eyes to a local artist of whom I had not previously heard. Winifred Knights was born in 1899 in Streatham, very close to our new neighbourhood, and she went to my old school James Allen’s Girls’ School. She was a British painter influenced by the Italian Quattrocento but it was her drawings that blew me away; delicate, almost microscopic feathered linework, which appeared to have been rendered by an assiduously graceful hand and yet seemed to me to pulse with life out of the page.

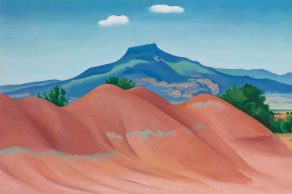

A few weeks later I went to the showstopping retrospective at Tate Modern on Georgia O’Keeffe and despite the thirteen rooms of expansive canvases and her reputation as one of the giants of modern American art, I left feeling decidedly underwhelmed. Having never seen a Georgia O’Keeffe painting in the flesh, I had been expecting a sumptuous, sensual delight for the senses, but every painting just seemed to me to be flat, uninspiring and – dare I say it? – a little amateurish. As we left the final room and walked past a shop display wall covered in posters of her popular flower paintings, I wondered why the monumental Tate show felt like a triumphant display of the Emperor’s New Clothes, and yet the comparatively minor Dulwich show felt like discovering a bright, shining little treasure.

The two women were born within twenty years of each other, and both showed early artistic promise. Born in 1879 in Wisconsin, the young Georgia decided by the age of ten that she was to become an artist. Winifred too had begun to draw at an early age and, according to the Streatham News of 1920, “Even before she could properly talk the young artist cried out for “Chalk, Chalk”, which her mother supplied, and she was happy.”

Both women had teachers who were influenced by the Impressionist movement. O’Keeffe attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and then learnt under the tutelage of William Merrit Chase at art school in New York; Knights went to the Slade School of Fine Art in London where she studied under Henry Tonks. Both won the prize at their respective Art Schools as well as a subsequent scholarship which developed their careers and led each to meet her husband.

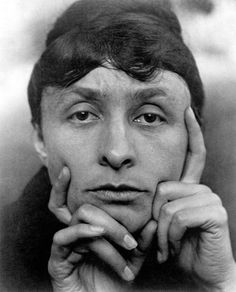

Georgia O’Keeffe started her career turning her back on her training in painting as felt she could not distinguish herself as an artist within the mimetic tradition, and instead she started work as a commercial artist and then spent several years teaching art, first as a teaching assistant and later as a head of department. Crucially in 1915 some of her charcoal drawings were shown by a friend to Alfred Steiglitz, the photographer and gallerist who was later to become her husband. Georgia was by nature a loner with a prickly personality, and her relationship with her husband has been described by her biographer as “a collusion … a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word.” Yet it was this union which was ultimately to become the key to her success.

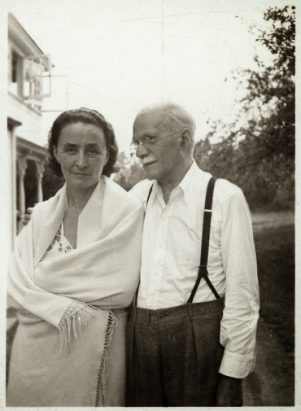

Steiglitz was 23 years her senior and as well as being a successful photographer he was an established art promoter, known for the New York galleries he ran in the early years of the 20th century. He made more than 350 photographs of her, some of which were nudes that created a public sensation in an exhibition of 1921. Through Steiglitz, O’Keeffe came to know many of his circle of artist and photographer friends by whose work she was inspired. It was he who first promoted her work, eventually organising annual exhibitions of her work which made her one of the most important American artists by the mid 1920s. And it was Steiglitz who first put forward the Freudian theory that her flower paintings – for which she is now best known – were in fact studies of the female vulva, an interpretation which was later to be picked up by the feminist artists of the 1970s, despite the fact that O’Keeffe herself denied its veracity. O’Keeffe outlived her older husband by 40 years, finally passing away at the age of 98 and leaving a legacy which included the Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1 which sold for 44 million dollars in 2014, the highest price ever paid for a painting by a woman at auction.

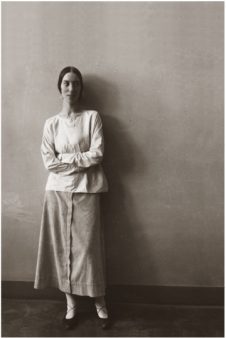

By contrast, when Winifred Knights passed away at the age of 47, she did not even receive an obituary. It was not until the 1980s, when one of her most lauded works The Deluge was rediscovered as part of a collection which had been consigned to auction, that her oeuvre of work began to be reassessed. The Deluge was the critically acclaimed entry which made her the first woman in England to win the prestigious Scholarship in Decorative Painting awarded by the British School at Rome. Winifred Knights moved to Italy to complete her scholarship. Her beauty and striking persona attracted attention from the moment she arrived and it was here that she first met her husband, the painter Thomas Monnington. On her return to England she was known for her distinctive dress, favouring the simple clothing style of the Italian peasant woman in contrast to the tubular silhouette fashionable in London circles. Knights worked slowly but steadily as an artist, exhibiting to critical success, and executing work for various patrons, including a commission on which she collaborated with her husband. They had a son together, after a previous pregnancy was tragically cut short by stillbirth, and she proved to be a devoted but over-anxious mother. An unsettled period with the onset of the Second World War mirrored the nervous breakdown she had suffered as a result of the First World War, and it brought her creative productivity to a standstill. Her marriage deteriorated as the war came to an end, and tragically the following year she suffered a brain tumour which killed her.

It is ironic that these two exhibitions were shown simultaneously in London, as they served only to underline to me how much success or failure can turn on a penny – how a fortuitous collaboration with the right person can ramp up a career to the superstellar levels or how fate can turn talent to nothing. It made me sad that Winifred Knights was clearly an artist with so much talent and yet was forgotten for so many years and I applaud the Dulwich Picture Gallery for putting on this, her first major retrospective (until 18th September).