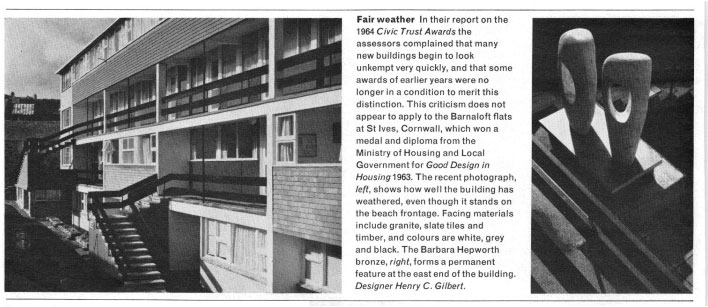

Returning home from our Cornish week away, I was intrigued to find out more about the apartment building we had stayed in, the Barnaloft/Piazza apartments on Porthmeor Beach in St. Ives. The building was designed in the early 1960s by Henry C. Gilbert, better known as Gillie and integral to the artistic life of St Ives for the half century that he lived and worked in the town as an architect and an art gallerist. Bernard Leach said about him: “We owe Mr Gilbert a great deal for what he has contributed to art in what used to be a fishing village” and Leach actually moved into number 4 Barnaloft in the latter part of his life after he had given up potting.

Gillie brought two of Hepworth’s sculptures into the design for the Barnaloft/Piazza apartments – the bronze ‘Two forms in Echelon’ and ‘Single Form with Two Hollows’ at the east end of the building, and he championed local artists, holding an exhibition in the Guildhall to celebrate the granting of the Freedom of the borough of St Ives to Hepworth, Nicholson and Leach in the late 1960s.

His design for the building won a medal from the ministry of Housing and Local Government in 1963. The award was for Good Design in Housing and the assessors recognised how the building had weathered well unlike previous winners of the award which had deteriorated rather quickly into an unkempt state.

One of the assessors for the award was Arthur Ling who was City Architect of Coventry between 1955 and 1964. We had been staying at the apartment building because my mother happens to know Ling’s daughter who now rents out the apartment to friends. Presumably Arthur Ling had judged the building worthy of the award in 1963 and then gone on to purchase one of the apartments as he liked it so much.

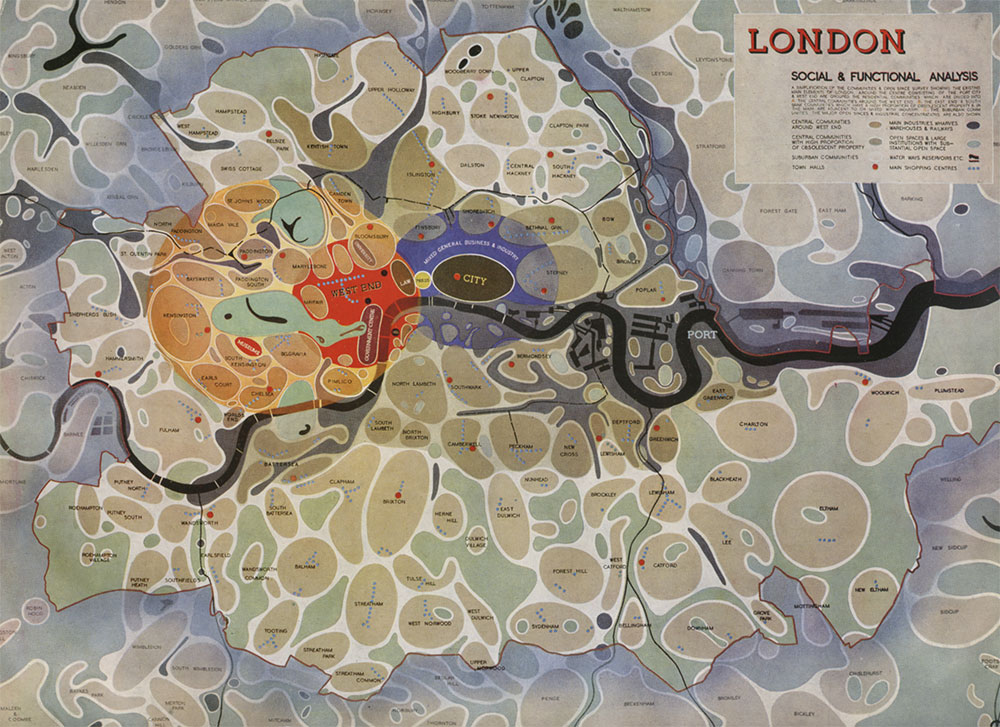

Arthur Ling also had a very interesting career, having previously been Chief Planning Officer for the London City Council – then the most prestigious office in the local authority sector – in the post war period when the authorities were considering how to rebuild the devastated city. London’s layout was at a ‘critical moment’ in its history, and in 1943 the County of London Plan, designed by Patrick Abercrombie and John H. Forshaw, was the first of two ambitious documents for post-war improvements to the capital. This was the forerunner to the Greater London Plan (the Abercrombie Plan) of 1944, and the film below was released by the Ministry of Information to explain the county plan. Abercrombie and Forshaw feature in the first two thirds of the film, and then Arthur Ling himself presents the planning concept of the Plan in the final third of the film.

Arthur Ling also had a very interesting career, having previously been Chief Planning Officer for the London City Council – then the most prestigious office in the local authority sector – in the post war period when the authorities were considering how to rebuild the devastated city. London’s layout was at a ‘critical moment’ in its history, and in 1943 the County of London Plan, designed by Patrick Abercrombie and John H. Forshaw, was the first of two ambitious documents for post-war improvements to the capital. This was the forerunner to the Greater London Plan (the Abercrombie Plan) of 1944, and the film below was released by the Ministry of Information to explain the county plan. Abercrombie and Forshaw feature in the first two thirds of the film, and then Arthur Ling himself presents the planning concept of the Plan in the final third of the film.

The film, ‘The Proud City’, is fascinating for the old-fashioned, stilted delivery of its protagonists, as well as their concept of the new London as a series of neighbourhoods of around 10,000 inhabitants echoing the cluster of villages that characterised the ancient area. Their preoccupations with combating the dirt and disorder of the city with a utopian vision of a better, fairer city is a theme that is still in circulation with today’s regeneration programmes.