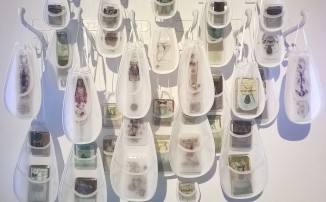

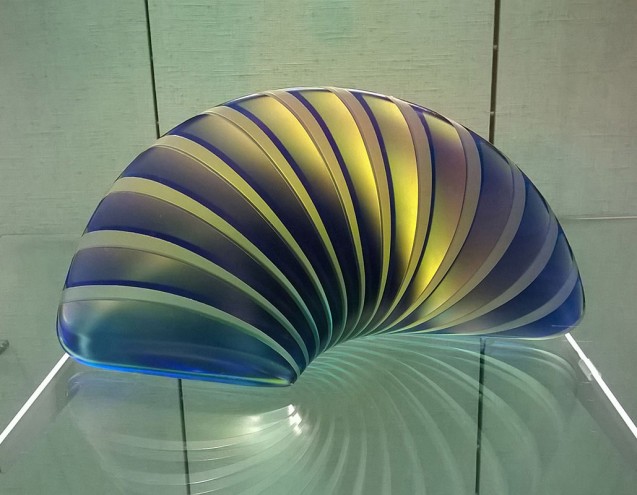

The Contemporary Glass Society had a great turnout for its Creative Hub session last Saturday, and I suspect that – like me – many people came along because of the opportunity to visit the studio of Angela Thwaites that was promised as part of the day. Angela is a well known glass artist who casts beautiful intimate objects from glass and teaches glass internationally. I also knew Angela from a few years ago when at one of our Teepee Glass exhibitions we invited Angela to exhibit as our guest artist, so I was keen to see where she makes her work, and clearly I was not the only one. The assembled crowd was so large that a local church hall had to be sequestered to accommodate us all for the Creative Hub discussions in the afternoon.

It wasn’t until the evening that the group snaked its way through the streets of south London to Angela’s house and so it was that we were ushered in smaller groups of four through her now dark and freezing garden to squeeze into her compact studio.

Glass casting requires a lot of equipment so I had expected a large space but I was taken aback at how small her garden studio was, and yet how everything fit so carefully into the tiny space. Various kilns, cold working equipment and a large sink all fit into this three dimensional puzzle of a space with all the surrounding gaps filled with shelves of materials and samples of moulds and glass.

Having just packed up and left my own studio – and knowing I will be without a studio for months now – it seemed at once familiar and poignant to be reminded how we artists try to create beautiful and perfect objects from within a space that often feels like organised chaos.

However seeing Angela’s bike propped up against the machinery, and realising that she must have to move that bike into the garden every time she works, I also remembered the reason I am moving…. there came a point when my studio tipped from being organised chaos to simply being chaotic, and ultimately I am putting up with being studio-less for the next few months in order to build a better space for myself in the long term.

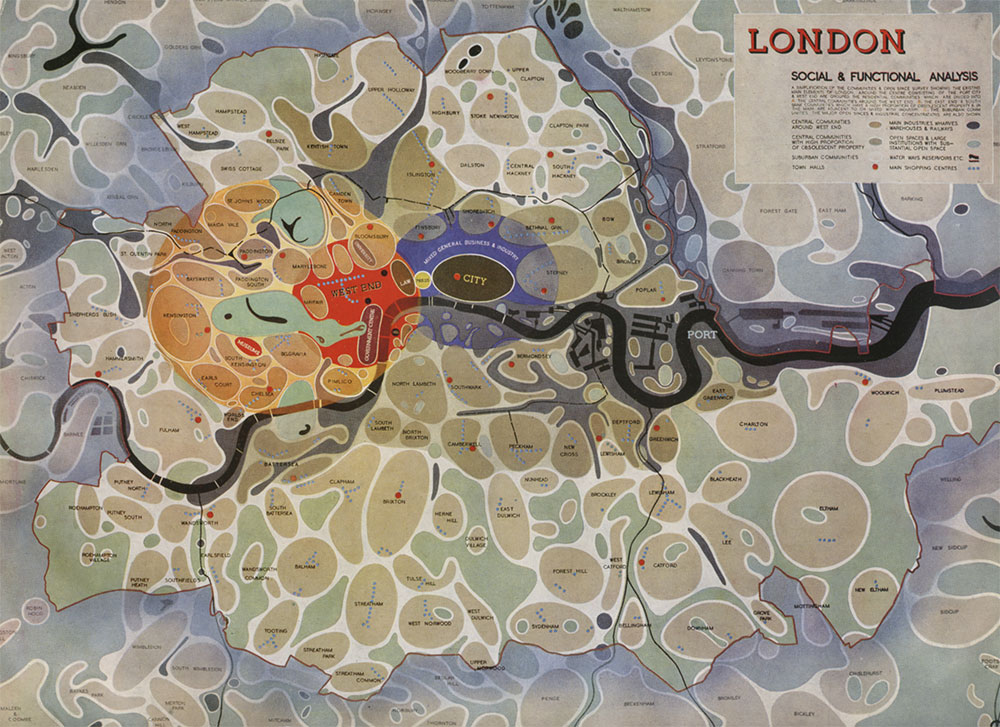

Arthur Ling also had a very interesting career, having previously been Chief Planning Officer for the London City Council – then the most prestigious office in the local authority sector – in the post war period when the authorities were considering how to rebuild the devastated city. London’s layout was at a ‘critical moment’ in its history, and in 1943 the County of London Plan, designed by Patrick Abercrombie and John H. Forshaw, was the first of two ambitious documents for post-war improvements to the capital. This was the forerunner to the Greater London Plan (the Abercrombie Plan) of 1944, and the film below was released by the Ministry of Information to explain the county plan. Abercrombie and Forshaw feature in the first two thirds of the film, and then Arthur Ling himself presents the planning concept of the Plan in the final third of the film.

Arthur Ling also had a very interesting career, having previously been Chief Planning Officer for the London City Council – then the most prestigious office in the local authority sector – in the post war period when the authorities were considering how to rebuild the devastated city. London’s layout was at a ‘critical moment’ in its history, and in 1943 the County of London Plan, designed by Patrick Abercrombie and John H. Forshaw, was the first of two ambitious documents for post-war improvements to the capital. This was the forerunner to the Greater London Plan (the Abercrombie Plan) of 1944, and the film below was released by the Ministry of Information to explain the county plan. Abercrombie and Forshaw feature in the first two thirds of the film, and then Arthur Ling himself presents the planning concept of the Plan in the final third of the film.